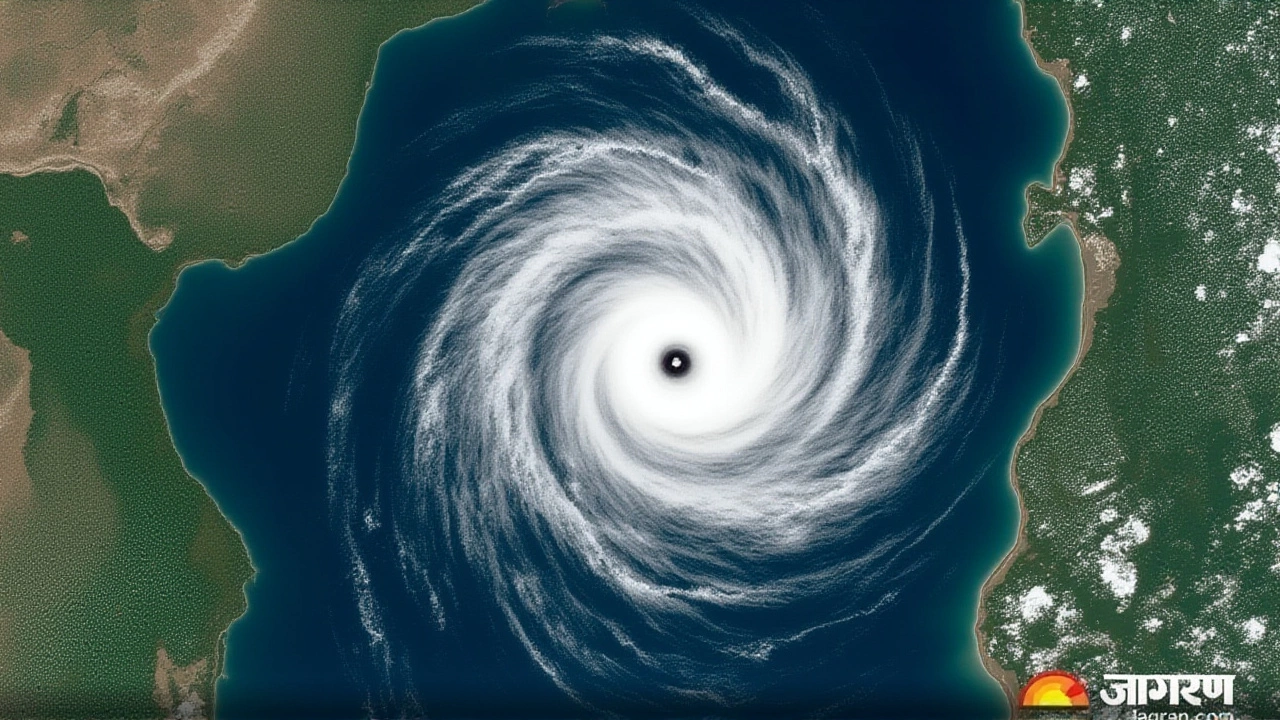

When India Meteorological Department issued its most urgent weather alert in years on October 28, 2025, it wasn’t just another monsoon warning. Cyclone Montha was barreling toward India’s southeastern coast with winds hitting 90–110 km/h, and the real danger wasn’t the wind—it was the rain. Over 21 centimeters of rainfall in isolated spots. Rivers swelling. Cities drowning. And 18 districts bracing for what officials called "unprecedented" conditions. The storm made landfall that evening, turning streets into rivers and leaving thousands without power, while emergency crews scrambled to evacuate low-lying neighborhoods in Coastal Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

Storm on the Doorstep: The Immediate Threat

The India Meteorological Department didn’t mince words. On October 28, it warned of "extremely heavy rainfall"—21 cm or more—in a narrow but deadly band stretching from Coastal Andhra Pradesh and Yanam through Telangana and Rayalaseema. That’s more than eight inches of rain in less than 24 hours. In places like Kurnool and Nellore, water levels rose so fast that residents reported their homes filling up before they could even grab their belongings. Meanwhile, Tamil Nadu saw 12–20 cm of rain on the 28th, while Bihar and West Bengal were warned of torrential downpours on the 30th and 31st. The storm’s reach was vast: from Saurashtra to Arunachal Pradesh, over 12 states were under some form of alert. "It’s not just rain," said one local official in Visakhapatnam. "It’s a wall of water coming in waves. We’ve seen floods before, but never this fast, this widespread."What the Forecast Didn’t Say: The Hidden Risks

Beyond the numbers, the real terror lay in what the IMD couldn’t fully predict. Landslides in the Eastern Ghats. Mudslides choking highways near Ongole. Underpasses in Hyderabad and Vijayawada turning into death traps as water surged past waist height. The India Meteorological Department flagged these risks in its October 27 alert, but few outside meteorology circles understood how quickly they’d materialize. By midday on the 28th, videos from the field showed buses stranded in floodwaters near Machilipatnam, while fishermen in Kakinada were ordered to stay ashore. Beaches from Puri to Kovalam were barricaded. Tourist resorts in Goa and Kerala, already recovering from monsoon damage last year, shuttered early. The U.S. Consulate in Kolkata issued its own advisory, urging citizens to avoid non-essential travel—a rare move that signaled how seriously foreign missions were taking the threat.Who’s Paying the Price?

It’s always the same people who suffer most. Farmers in Chhattisgarh lost entire paddy fields overnight. In Rayalaseema, small traders saw their shops flooded with sewage and mud. In Bihar, where rivers like the Kosi and Gandak are already prone to bursting, the IMD warned of "riverine flooding"—a term that means entire villages could be cut off for days. "We’ve been told to evacuate," said Ramesh Kumar, a rice farmer from Gaya. "But where do we go? Our home is our only asset. And the government’s relief camps are already full from last year’s floods." The economic toll is still being calculated, but early estimates suggest over ₹1,200 crore in agricultural damage alone. Insurance claims are expected to spike. And with the monsoon season officially over, this storm feels like a cruel anomaly—part of a troubling trend.

Why This Storm Feels Different

Cyclone Montha isn’t just a weather event. It’s a symptom. India has seen 11 cyclones since 2020, with four making landfall as severe or very severe storms. Climate scientists at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology note that warming in the Bay of Bengal has increased cyclone intensity by 20% over the last decade. Sea surface temperatures near Andhra Pradesh hit 31.5°C this month—nearly 2°C above normal. That’s fuel. "We’re not just seeing more storms," said Dr. Anjali Sharma, a climate researcher in Pune. "We’re seeing storms that behave unpredictably. Montha intensified faster than any model predicted. That’s the new normal."What Comes Next?

The IMD expects rainfall to taper off by November 2, but the aftermath will linger. Waterlogged fields mean delayed planting. Damaged roads will take weeks to repair. In urban centers like Hyderabad and Chennai, drainage systems designed for 20-year storms are now being tested by 100-year events. Authorities are now reviewing emergency response protocols. The National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) deployed 120 teams across five states. But many local governments admit they’re understaffed and under-equipped. "We need better early warning systems," said a senior official in Visakhapatnam, speaking off-record. "We got the alert. But did we have the capacity to act on it fast enough? That’s the real question."

Background: A Pattern of Overwhelm

This isn’t the first time India has been blindsided. In 2023, Cyclone Biparjoy flooded Gujarat, killing over 80 people. In 2022, Cyclone Asani hammered Odisha and Andhra Pradesh. Both events triggered similar warnings—and similar failures in evacuation and infrastructure readiness. The difference with Montha? The scale. The speed. The geography. Unlike past storms that hit one region, Montha’s rain bands stretched from the west coast to the northeast. It’s a storm that doesn’t respect state borders—and neither do our response systems.Frequently Asked Questions

How many districts are under extreme rainfall alert, and which ones are most at risk?

At least 18 districts across five states are under extreme to very heavy rainfall alert, with Coastal Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Rayalaseema, and Chhattisgarh bearing the brunt. Districts like Kurnool, Nellore, and Adilabad saw over 21 cm of rain in 24 hours, triggering flash floods and landslides. Coastal zones remain most vulnerable due to storm surge and drainage failure.

What are the biggest dangers beyond flooding?

Beyond flooding, the greatest risks are landslides in hilly regions like the Eastern Ghats, structural collapse of weak kutcha homes, and power grid failures due to downed lines. Lightning strikes during thunderstorms have already caused three fatalities in Tamil Nadu. In Bihar and West Bengal, riverine flooding could isolate dozens of villages, cutting off food and medical supplies for up to a week.

Why did the U.S. Consulate issue a warning?

The U.S. Consulate General in Kolkata issued its alert because of the widespread disruption affecting diplomatic operations and citizen safety. With roads impassable, flights canceled, and emergency services overwhelmed, foreign missions are required to advise their nationals to avoid travel and remain indoors. This is a standard protocol—but the fact they issued it for a cyclone underscores the severity.

Is this linked to climate change?

Yes. The Bay of Bengal’s sea surface temperatures are now 1.5–2.5°C above the 30-year average, fueling faster cyclone intensification. Cyclone Montha strengthened from a depression to a severe cyclonic storm in under 36 hours—a pace that’s doubled since 2010. Climate models predict such rapid intensification events will become 40% more frequent by 2040, making early warnings and infrastructure upgrades critical.

What should residents do if they’re still without power or clean water?

Residents should contact local NDRF helplines (available in all affected districts) or use the NDMA’s WhatsApp alert system. Boil all drinking water—even if it looks clear. Avoid wading through floodwater, which may contain sewage, chemicals, or live wires. Keep emergency numbers saved: 1070 for police, 108 for medical aid, and 112 for general emergency. Local NGOs are distributing clean water and meals in high-risk zones.

How long will recovery take?

Recovery will take months. Roads and bridges in rural areas may need 6–8 weeks to repair. Agricultural losses alone could delay the next planting cycle by 4–6 weeks, affecting food prices. Urban centers like Hyderabad and Vijayawada will see normalcy return in 2–3 weeks, but only if drainage systems are cleared. Long-term, experts say India needs to invest in climate-resilient infrastructure—or face even worse storms next year.